.

There’s a few twists and turns in this story, which centers primarily around a son’s ode to his father,

|

|

(https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.$b281525;view=1up;seq=1)

I first came across this book while exploring Hathitrust chess books from 1899, i.e. searching for new tournament book sources. Apparently some biographical item scored a hit for 1899 – and even though we seen the book dates from 1946 (or 1945), I decided to skim through a few pages, given I was in the neighborhood. This is the “butterfly” effect of doing research on chess history – some of the most interesting items are found by accident.

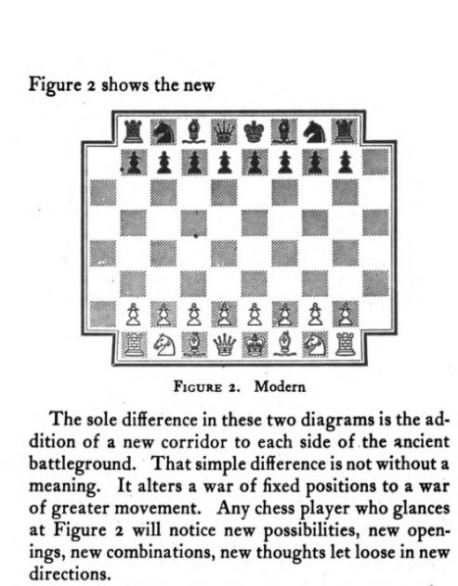

In this particular case I was struck by Mr. Morley’s “contribution”, succinctly summarized in Figure 2 on page 3: I suppose this new variant could be called Morley’s Corridor chess, or more simply just Morley chess. It looks like it might make for a fun evening to try out this board variant with friends (or foes). I looked to see if some mention is made of the variant on the wiki chess variant page, but it seems missing – chess variants (wiki). It seems that the new board offers the knight some new development options, and perhaps also lessens the opportunity for back rank mates – but otherwise it represents terra incognito for play. One of the main new features, according to the inventor, is to restore the dignity of the rook-pawns – “‘a fine rage at this mistreatment“, i.e. allowing them two capture squares akin to the other pawns. The two additional corridors, as Morley calls them, do represent a certain challenge for algebraic notation, one which I haven’t resolved in my own mind how to best designate/resolve.

I suppose this new variant could be called Morley’s Corridor chess, or more simply just Morley chess. It looks like it might make for a fun evening to try out this board variant with friends (or foes). I looked to see if some mention is made of the variant on the wiki chess variant page, but it seems missing – chess variants (wiki). It seems that the new board offers the knight some new development options, and perhaps also lessens the opportunity for back rank mates – but otherwise it represents terra incognito for play. One of the main new features, according to the inventor, is to restore the dignity of the rook-pawns – “‘a fine rage at this mistreatment“, i.e. allowing them two capture squares akin to the other pawns. The two additional corridors, as Morley calls them, do represent a certain challenge for algebraic notation, one which I haven’t resolved in my own mind how to best designate/resolve.

Of course, not everybody might agree that play on this board would offer a fun evening of distraction, I found one site which characterized it as “Morley’s one (bad) chess idea” (though without rationale), and another which gives it as “A novelty whose fame owes most to the author’s standing.” – though the latter does mention Lasker’s friend Harold M. Phillips as anticipating the new play (quoting Pritchard):

The new game attracted the attention of Lasker’s friend Harold M. Philips [sic] who wrote to Morley (then embarking on the Queen Mary) ‘..You had better let me know every day where you are in Europe so that I can telephone you long distance if a new thought occurs to me – not about business or even politics or matters of international policy or even a possible discovery of a manuscript in the handwriting if Shakespeare, but about the corridor’.

OK, that was really going to be the extent of my originally planned post – but it turns out that this book had much more to offer than just that one new idea. Let’s see a few promotional blurbs from inside the book, one of which being written by a very recognizable personage:

Kashdan’s name is recognizable to US chess players, certainly those familiar with the US chess scene circa WWII.

Even the most casual perusal of the book will reveal it is more than just a promotion of the new variant, but, as alluded to in the beginning of this post, an ode to Frank Vigor Morley’s father, Frank Morley (which seems to be the entire extent of his name). The father was the more experienced chess player, and his beginnings in late 19th century England, and his continuation to America, make for an interesting tale. In fact, the father even has a page on CG:

http://www.chessgames.com/perl/chessplayer?pid=19135

Again, quoting Pritchard, whose work is available on John and Susan Beasley’s website:

The book is a civilised wander through the garden of chess and other things.

The “other things” first became apparent to me when I came across the name Airy when browsing the book. Everybody who has studied physics and math during their student days will remember the name, though maybe not the equation. Yet here was a mention of Airy on p12, could it possibly be the same?

What I started out to say is that my father was a natural chess player, and that while he was a boy he achieved a local reputation for the game. When he was not more than ten or twelve his father encouraged him to make tours from Woodbridge to such centers as Ipswich, Debenham, and Wickham Market to play against the best that they could muster. The summer before he died, he mentioned the great battle he once had with the butcher in Debenham. Of more importance than the butcher, Sir G. B. Airy, the Astronomer Royal, retired, about the year 1870, to live at Playford, a couple of miles from Woodbridge. Airy, though he was beginning to get on in years, had by no means lost his unusual gift for exact and elaborate computation.* By all accounts the hard-headed old gentleman and the Quaker tradesman’s son had a very good time playing chess together. When my father’s father died, in 1878, and the death-rattle of the china trade was heard in the town, it was Airy who insisted that though the others of the family might at once go to work, my father should prepare himself to go on from school to Cambridge.

* Incidentally, Airy calculated the boundary between the U.S.A. and Canada.

A quick check on wiki confirmed it was one-and-the-same. Thanks then, partly to Airy’s encouragement, Frank Morley went to King’s College in Cambridge. Hence, the “other things” mentioned by Pritchet, mainly focus on the father’s career in academics, as Frank Morley became a mathematician, who was especially noted for his educational efforts in the USA, where he sponsored ~50 PhD’s:

Used w/o permission from faculty.evansville.edu

While living in Cambridge, the father became a member of the Cambridge Chess team, and a frequenter of Simpson’s Divan. It’s worth quoting FVM (i.e. Frank Vigor Morley, the son), waxing poetic about Simpson’s Divan to begin chapter 4 of his book (p22):

Let us now praise famous men. . . .

EcclesiasticusMy father went off chess for the year that he was out of college, but during the three years at Bath and until he left England in 1887, he seems to have played a good deal, and whenever he passed through London, despite the scarcity of half-crowns, he managed to place his stake upon the board and mix with the professionals at Simpson’s Chess Divan. Famous Simpson’s Divan! How I should have loved to see that old place in the Strand at the height of its dingy prime!

FVM also gives a game played between Morley and Bird, up to the 21th move, then “and White wins”:

Aside – the book also mentions another Bird game, an epic game spanning four sittings where Bird defeated Potter in a 6-game match to lay claim to the 1879 London Chess Club Handicap tournament 1st prize. FVM provides a little insight into Bird in introducing the game:

Unfortunately, I am unable to find Steinitz’s original Field version of the game, an unfortunate result of the asymmetry between the multitude of American sources, freely available online, and dearth of openly available British sources (e.g. almost all google book versions of British periodicals are from scans made from copies in American universities – unlike Dutch or Austrian online archives, Britain offers almost no public domain access). However, all is not lost, as Winter makes note of this game as of “considerable interest”, although he omits Steinitz’s notes, he does give the game, in CN 9048, part of which includes the following excerpt from CPC v3 (1879) p133 describing the game

Note that the game, as given by Winter, is only 143 moves. But not only does Morley give the game as 145 moves, so does Bird in his book Chess Practice (1892) p76 (link)

|

There is a lot more of the story of Frank Morley to be told, including his move to America and professorial stints at Haverford and John Hopkins (besides the book, also see here). He also started a family of boys – Christopher D., Felix M., and Frank V., all of whom went on to be significant contributors to society (novelist, editor/university president, and mathematician/writer). We will turn our attention to also include Frank V. [perhaps in this post, perhaps in a future post], whose book has been our focus. In fact, the book’s publication itself will be a topic of discussion.

For instance, Winter also mentions FVM’s book in another context, as an example of chess boards with a black square on h1 (rather than the correct white square) – see CN 4650. Winter shows other examples, but here is Morley’s:

Another example of the cover art can be found on Abebook’s site, specifically the example for sale by Bygone Books: link.

Winter notes that the appearance of a dark square on the bottom right of the board is a affectation of the gilding process – where the gilding print is essentially an inverse of an image where the square is white. Winter also has another note specifically about two inscribed copies of the book in his possession, in CN 4651. He finishes his post with the following entry:

Although chess sources offer virtually no factual information about him, we note an academic webpage which reports that ‘Frank Vigor Morley (1899-1985) became a director of the publishing firm Faber and Faber but was also a mathematician who collaborated with his father for over 20 years’. Regarding Frank Morley senior (1860-1937) the same source affirms:

‘We mentioned that Morley was a chess enthusiast while at school and, indeed, he was an exceptionally good chess player … He played at the highest level and beat Lasker on one occasion while Lasker was world chess champion.’

–CN 4651

Of course FVM was not a strong chess player, and has no competitive games in any chess database (least that I know about) – so it’s not so unexpected that chess sources offer little information about him. The internet, on the other hand, offers bountiful information about him, to which we will return momentarily. Presently, let’s explore the claim that Frank Morley defeated Emanuel Lasker, which is repeated on his wiki page. Where is this information from, and are the moves available? No online-db has it, and a search on google books fails to turn anything up. But we do have this information from the book, found on p32:

So my father gave up chess. He didn’t need it. He gave up serious chess. Of course he played with Uncle Spiers, with Walter Shipley and other Quaker worthies, and of course when Emanuel Lasker, then succeeding Steinitz as World’s Champion, came to stay overnight at Haverford, my father (who knew him as a mathematician) played with him. As a matter of fact, my father won the game they played, but he always attributed that to some courteous idea of Lasker’s of repaying hospitality. Which may have been so, for Lasker had too much chess-genius to have been caught napping by the deceptive innocence of the Friendly atmosphere. I don’t wish to overstate the episode. From all of the foregoing I merely want to establish that my father was a hard-hitting chess player who in his time had studied the game seriously, but who in his mature life, and for understandable reasons, had given it up.

A treatment which places the victory in its proper context.

To finish Frank Morley’s discussion, let’s consider this piece of advice he, referred to as Doctors in the following, offered to his son at the end of a chess game:

And at the sad inevitable end, when the book was lowered for the last time, Doctors would put his head a little on one side and with thumb and forefinger pull at his nose, and Madame Doctors would look up from her knitting and say, “Don’t do that, Frank,” and as the poor cut snake (that’s me) was slowly writhing on the pitchfork he would continue to pull at his nose and remark: “I studied it too much for you to beat me. But I advise you not to study chess. It can get too absorbing.“

Perhaps that is good advice, and a good place to stop this installment.

zzz